Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia Are Associated with Increased Caregiver Burden

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). Frequent and severe neuropsychiatric symptoms create high levels of distress for patients and caregivers, decreasing their quality of life. The aim of this study was to investigate neuropsychiatric symptoms that may contribute to increased caregiver burden in PDD patients.

Methods

Forty-eight PDD patients were assessed using the 12-item Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) to determine the frequency and severity of mental and behavioral problems. The Burden Interview and Caregiver Burden Inventory were used to evaluate caregiver burden.

Results

All but one patient showed one or more neuropsychiatric symptoms. The three most frequent neuropsychiatric symptoms were apathy (70.8%) and anxiety (70.8%), followed by depression (68.7%). More severe neuropsychiatric symptoms were significantly correlated with increased caregiver burden. The domains of delusion, hallucination, agitation and aggression, anxiety, irritability and lability, and aberrant motor behavior were associated with caregiver stress. After controlling for age and other potential confounding variables, total NPI score was significantly associated with caregiver burden.

Conclusions

The results of this study confirm that neuropsychiatric symptoms are frequent and severe in patients with PDD and are associated with increased caregiver distress. A detailed evaluation and management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in PDD patients appears necessary to improve patient quality of life and reduce caregiver burden.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are frequently observed in Parkinson’s disease (PD), even during the early, untreated stage 1. PD patients with dementia show more frequent and severe neuropsychiatric symptoms than those without dementia [2–4]. In patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), almost 90% present with at least one neuropsychiatric symptom, and 77% show two or more symptoms [3]. Olfactory dysfunction, a common non-motor symptom, has also been associated with an increased number of neuropsychiatric symptoms [5].

Caregivers are more distressed when PDD neuropsychiatric symptoms are more frequent and severe [2,3,6]. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with reduced quality of life [7,8], difficulty in performing activities of daily living [9], increased admission to nursing homes [10], and increased mortality in nursing-home patients [11].

Dementia and mild cognitive impairment in PD have been shown to increase caregiver burden and decrease quality of life [12]. In addition, other factors, such as age, age of disease onset, duration of illness, and severity of motor symptoms, are known to be associated with caregiver distress [13–15]. Furthermore, the caregiver’s age, gender, health status, and caregiving duration also influence their quality of life and stress [16]. Because many factors interact to independently or dependently influence caregiver burden and distress, this study asked whether neuropsychiatric and motor symptoms cause increased caregiver burden in the case of PDD. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and motor or cognitive dysfunction relating to caregiver burden were assessed using the Burden Interview (BI) and Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) [17–20].

MATERIALS & METHODS

Patients

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital. Each patient provided written, informed consent prior to participating.

Forty-eight patients diagnosed with PDD at the movement disorder outpatient clinic of the university hospitals based on the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank clinical diagnostic criteria and the clinical diagnostic criteria for probable PDD were enrolled [21,22]. Clinical information included age, gender, disease duration, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, dyslipidemia, and current medication. Data from complete physical and neurological examinations, laboratory tests, and brain magnetic resonance imaging were obtained. Patients 1) with a previous stroke or other neurological and psychiatric disorders, 2) atypical PD or secondary Parkinsonism or 3) secondary causes of dementia were excluded.

All patients were on anti-parkinsonian medications. The levodopa equivalent daily dose was calculated as follows: dose of levodopa plus dose of dopamine agonists multiplied by equivalents (= 1 × levodopa dose + 0.75 × controlled release dose + 0.33 × entacapone + 20 × ropinirole dose + 100 × pramipexole + 10 × selegiline + 1 × amantadine) [23]. When enrolled in this study, all patients had been diagnosed for the first time with dementia. No PD patient had ever taken anti-dementia drugs, antipsychotics, antidepressants or anxiolytics prior to this study.

Clinical evaluation

Information on memory problems and other subjective cognitive deficits was obtained from caregiver interviews.

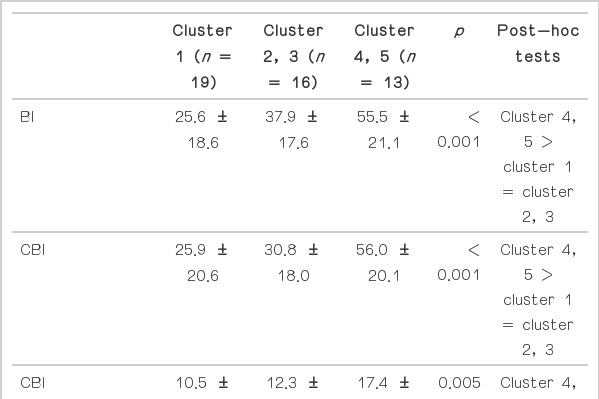

To assess neuropsychiatric symptoms, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) was used [24]. The NPI comprises sub-questions in 12 different categories covering four major neuropsychiatric symptom domains: mood, apathy, agitation, and psychosis. Symptom frequency was rated on a scale of 1 to 4, and severity was rated on a scale of 1 to 3. A composite score ranging from 1 to 12, defined as the product of frequency and severity, was calculated. In addition, NPI sub-scores for each patient were analyzed using five different clusters of neuropsychiatric symptoms: 1) few and mild neuropsychiatric symptoms (n = 19), 2) high scores on depression, anxiety, apathy and low scores on the other items (“mood” group, n = 9), 3) high scores on apathy and low scores on the remaining items including depression (“apathy” group, n = 7), 4) moderate or severe sub-scores on the majority of items including irritability and agitation items (“agitation” group, n = 11), and 5) high scores on hallucinations and delusions together with low scores on the majority of other items (“psychosis” group, n = 2) [25].

The general cognitive status and dementia severity were evaluated using the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale and Global Deterioration Scale. Parkinsonian motor symptoms were evaluated using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part III and the modified Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) scale when patients were on medications. All patients were divided into tremor-dominant and akinetic rigid-dominant groups based on previous methods [26].

Caregiver burden was evaluated using BI and CBI. BI is a 22-item questionnaire used to measure caregiver stress caused by patient disabilities [17]. Each item is scored from 0 to 4. Total score is calculated as the sum of all scores and ranges from 0 to 88. CBI is a 24-item multidimensional questionnaire comprised of 5 different subscales [18–20] that quantify caregiver burden: 1) time-dependence burden: time spent on caregiving (items 1–5), 2) developmental burden: caregiver feelings during care (items 6–10), 3) physical burden: status of general health problems (items 11–14), 4) social burden: problems in the family and social life (items 15–19), and 5) emotional burden: negative feelings about the patient (items 20–24). Each individual item is scored from 0 to 4, the total score is the sum of all sub-scores and ranges from 0 to 96. The responder for these questionnaires was selected from one of the family members using the following criteria: 1) being a relative of the patient and older than 18 years; and 2) serving as the primary caregiver and with an intimate knowledge of the patient that developed over time.

Statistical analyses

Demographics were described using the mean, standard deviation (SD), number, and percentage. Correlation analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms, other motor and cognitive features, and caregiver burdens. Independent-sample t-tests were used to compare caregiver burdens and neuropsychiatric symptoms between tremor- and akinetic rigid-dominant groups. Burden differences among NPI clusters were also compared using a one-way analysis of variance. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of associated variables on caregiver burden. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

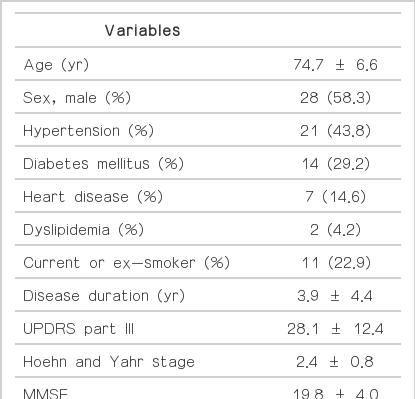

Of the 48 patients, 28 were men and 20 women. Their mean age (± SD) was 74.7 ± 6.6 years and the mean duration of PD was 3.9 ± 4.4 years. Fourteen patients (29.2%) had diabetes, 21 (43.8%) had hypertension, 7 (14.6%) had heart disease, and 2 (4.2%) had an abnormal lipid profile. Eight patients were current smokers, 3 were ex-smokers, and 37 were non-smokers. The severity of parkinsonian motor and cognitive symptoms was as follows: mean UPDRS part III score, 28.1 ± 12.4; mean H&Y stage score, 2.4 ± 0.8; mean MMSE score, 19.8 ± 4.0; and mean CDR score, 1.1 ± 0.7 (Table 1). All patients were on anti-parkinsonian medications with levodopa only or with dopamine agonists, amantadine, entacapone or selegiline. The mean levodopa equivalent daily dose was 490.3 ± 318.6 mg.

With the exception of 1 patient, all presented with one or more neuropsychiatric symptoms. The most frequent neuropsychiatric symptoms were anxiety and apathy (70.8%), followed by depression (68.7%), nighttime behavior disorder (58.3%), and appetite change (47.9%). Delusion, hallucination, agitation and aggression, disinhibition, irritability and lability, and aberrant motor behavior were present in 20–40% of patients. Euphoria occurred relatively infrequently (8.3%).

The total NPI score did not differ between male and female patients (male vs. female = 24.4 ± 24.2 vs. 22.6 ± 24.3, p = 0.729), and we observed no associations with age (r = −0.004, p = 0.980), disease duration (r = 0.062, p = 0.678), levodopa equivalent daily dose (r = 0.032, p = 0.827) or MMSE score (r = 0.090, p = 0.542). However, the total NPI score did correlate with CDR (r = 0.444, p = 0.002), H&Y stage score (r = 0.326, p = 0.024), and UPDRS part III (r = 0.312, p = 0.031).

All caregivers reported mild to moderate burdens, ranging from 0 to 79 using BI (mean; 37.8 ± 22.2) and 3 to 87 using CBI scores (mean; 35.7 ± 23.0). The mean CBI sub-scale scores were: time-dependence burden, 13.0 ± 6.2; developmental burden, 7.6 ± 6.4; physical burden, 6.2 ± 5.1; social burden, 4.4 ± 4.0; and emotional burden, 4.5 ± 4.7.

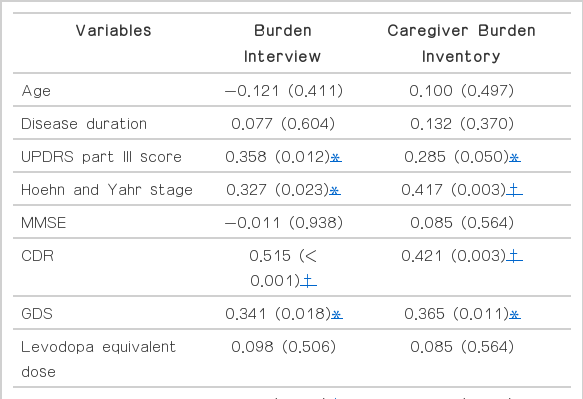

Neuropsychiatric symptoms correlated significantly with greater caregiver burden (Table 2). Delusion, hallucination, agitation and aggression, anxiety, irritability and lability, and aberrant motor behavior were associated with greater caregiver stress (Table 2 and 3). For the NPI clusters, caregivers of groups with irritability, agitation and psychotic symptoms (clusters 4 and 5), reported more severe stress or burden (Table 4).

Increasing age, longer disease duration, and lower MMSE scores did not affect caregiver burden. Burden correlated with more severe motor symptoms and cognitive dysfunction quantified using UPDRS part III and H&Y stage scores and CDR. Caregiver burden tended to be greater for the akinetic rigid-dominant group, although there were no differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms between tremor-dominant and akinetic rigid-dominant groups with the exception of the apathy domain (Table 5).

Comparison of caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric parameters based on Parkinsonian motor phenotype

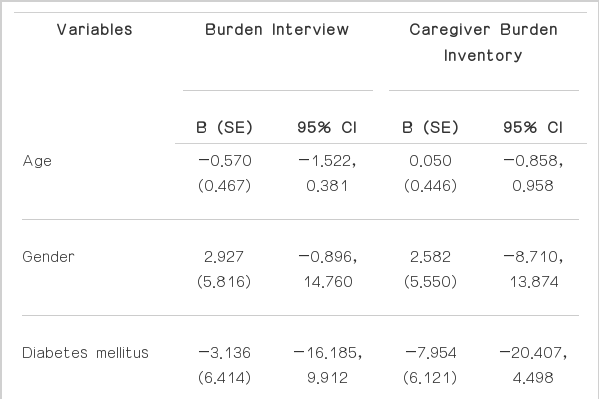

Linear regression analyses revealed that NPI score associated independently with caregiver burden in patients with PDD, as measured using BI and CBI, regardless of age, gender, vascular risk factors, and motor and cognitive status (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

Parkinson’s disease dementia patients included in this study presented with frequently occurring neuropsychiatric symptoms. All but one patient showed at least one or more neuropsychiatric symptoms. The frequency and severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms were similar to previous studies [2,3]; the most frequent and severe symptoms were apathy, anxiety, and depression. In contrast, euphoria was the rarest symptom.

A number of demographics and factors were associated with increased caregiver burden. Parkinsonian motor-symptom status or dementia severity in patients was associated with greater caregiver distress. However, neither patient age nor disease duration increased neuropsychiatric symptoms or family burden. This finding may be because the patients in this study had relatively short durations of PD: (3.9 ± 4.4 years) compared with a previous study (10.9 ± 7.7 years);14 the shorter disease duration may cause selection bias, and it is therefore possible that the longer disease duration group was underrepresented.

Severe neuropsychiatric symptoms correlated with caregiver distress; caregivers reported greater burden as neuropsychiatric symptoms became more frequent and severe. Only euphoria, which was the most rare and mildest symptom, was not associated with caregiver burden. Both sub-items and scales for depression and anxiety (Beck Depression Inventory and Beck Anxiety Inventory) showed a borderline association between mood and caregiver burden. Psychotic symptoms, such as hallucination, delusion, and agitation or irritability, correlated with more-severe caregiver distress. After controlling for age and other potential confounding factors, total NPI score associated significantly with PDD caregiver burden. This finding is consistent with recent studies showing neuropsychiatric symptoms were associated with increased caregiver stress or nursing home placement [27–32]. These data suggest that caregiving for PDD patients may impair psychological health due to fatigue and also deprive the caregiver of time to do activities that are desired and expected at that moment in life. Thus, the caregiver role may be characterized by perceived disruption-of-life expectations.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms were similar between Parkinsonian motor phenotype groups; however, the akinetic-rigid group showed higher NPI scores and more apathy. Caregiver burdens were marginally influenced by motor phenotype suggesting bradykinesia and rigidity were more stressful to caregivers than tremor symptoms.

This study has several strengths and weaknesses. The major strength was that both BI and CBI were used to estimate caregiver or family distress, which provided more precise and detailed results from a total of 46 items between these two assessments. In addition, PD patients diagnosed with dementia for the first time at enrollment were included. They had not taken any anxiolytics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, or anti-dementia drugs. Because these drugs improve symptoms, the total NPI score may have been reduced in patients using these medications. Several limitations were identified. First, all patients were taking anti-parkinsonian medications. Anti-parkinsonian medications are associated with behavioral disturbances and neuropsychiatric symptoms [33]. Hallucination and psychosis are frequent complications of anti-parkinsonian medications. However, a recent study showed that hallucination may correlate with cognitive decline rather than adverse dopaminergic events [34]. Other studies suggest that psychosis in PD patients results from multiple etiologies [35,36]. Moreover, the mean score and frequency of delusion and hallucination in this study were not very different from those of a previous study [3]. Second, this study was cross sectional. The frequency and severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms may not generalize to other populations; however, many cross-sectional studies have been performed and their outcomes accepted [2–4].

In conclusion, the results from this study confirm neuropsychiatric symptoms are frequent and severe in patients with PDD and that they are associated with increased caregiver distress. These data suggest that the detailed evaluation and management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in PDD patients may improve patient quality of life and reduced caregiver burden.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from Novartis Korea.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.