Perry Disease: Concept of a New Disease and Clinical Diagnostic Criteria

Article information

Abstract

Perry disease is a hereditary neurodegenerative disease with autosomal dominant inheritance. It is characterized by parkinsonism, psychiatric symptoms, unexpected weight loss, central hypoventilation, and transactive-response DNA-binding protein of 43kD (TDP-43) aggregation in the brain. In 2009, Perry disease was found to be caused by dynactin I gene (DCTN1), which encodes dynactin subunit p150 on chromosome 2p, in patients with the disease. The dynactin complex is a motor protein that is associated with axonal transport. Presently, at least 8 mutations and 22 families have been reported; other than the “classic” syndrome, distinct phenotypes are recognized. The neuropathology of Perry disease reveals severe degeneration in the substantia nigra and TDP-43 inclusions in the basal ganglia and brain stem. How dysfunction of the dynactin molecule is related to TDP-43 pathology in Perry disease is important to elucidate the pathological mechanism and develop new treatment.

INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS PERRY SYNDROME?

Perry syndrome was first reported in 1975 by Perry et al.[1] in Canada and was named after his achievement. The original family presented autosomal dominant inheritance, clinical rapidly progressive parkinsonism, depression, weight loss, sleep disturbance, and central hypoventilation [1,2]. Later, six families were reported who had similar symptoms in Canada (1979), the United States (1988), France (1992), the United Kingdom (1993), and Turkey (2002) [3-7]. In 2002, we first reported the Fukuoka-1 (FUK-1) family in Fukuoka, Japan [8].Lechevalier, who reported the French family, wrote an article in 2005 entitled “Perry and Purdy’s syndrome (familial and fatal parkinsonism with hypoventilation and athymhormia) [9],” and Elibol et al. [7] used the term Perry syndrome in the article and title.

Perry syndrome (Perry disease) is a hereditary neurodegenerative disease with an autosomal dominant inheritance, parkinsonism, psychiatric symptoms, unexpected weight loss, central hypoventilation, and transactive-response (TAR) DNA-binding protein of 43kD (TDP-43) aggregation in the brain. This disease is caused by dynactin I gene (DCTN1), which encodes dynactin subunit p150. The dynactin complex is a motor protein that is associated with axonal transport, and the p150 subunit plays an important role in dynactin function, including its role as a microtubule binding site. Since the discovery of the DCTN1 mutation in 2009, this gene mutation has been screened widely, and the number of reports is increasing. Presently, at least 8 mutations and 22 families have been reported; other than the “classic” syndrome, various phenotypes are recognized. Some cases of an incomplete type lack depression and body weight loss, and other cases present progressive supranuclear palsy or frontotemporal dementia. There was a report of a family with Perry disease with oculogyric crisis, impulse control disorder, and autonomic nerve symptoms in a clinical course.

Interestingly, before it was found that Perry syndrome is caused by DCTN1 mutation, the same gene mutation had previously been identified in a familial motor neuron disease (MND). By contrast, there was a report that some families had symptoms of Perry syndrome, but they had the MAPT mutation.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PERRY DISEASE: ORIGINAL CANADIAN FAMILY

In 1975, Canadian doctor Perry et al. [1] reported a family originating in British Columbia with a hereditary neurological disease that showed a unique clinical course. The affected members manifested the autosomal dominant disease for three generations, and the proband developed depression and apathy, withdrawing from his job at the age of 50 years. During the clinical course, he developed parkinsonism and additional symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, weight loss, and respiratory dysfunction due to hypoventilation. He did not respond to levodopa well and died abruptly of respiratory failure at the age of 56 years. Histopathological findings of the brain showed severe neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra without the presence of Lewy bodies. In the follow-up study, the same family had 10 affected members. Their clinical course was similar; psychiatric symptoms such as depression and apathy preceded, followed by parkinsonism, weight loss, and central hypoventilation. Sometimes, sleep disturbance such as insomnia was involved [2]. Levodopa was usually not effective, and the average age of onset was 50 years (range: 45–54 years) with a mean duration of disease of 5 years (range: 3–6 years). By 2002, an additional five families with similar phenotypes of the proband in the original article by Perry were reported [3-7]. Some cases did not show weight loss or central hypoventilation; however, the clinical and pathological findings were the same. Geographically, the founder effects were not plausible, and some gene abnormalities might have caused the flaccidity.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PERRY DISEASE: THE JAPANESE FUK-1 FAMILY

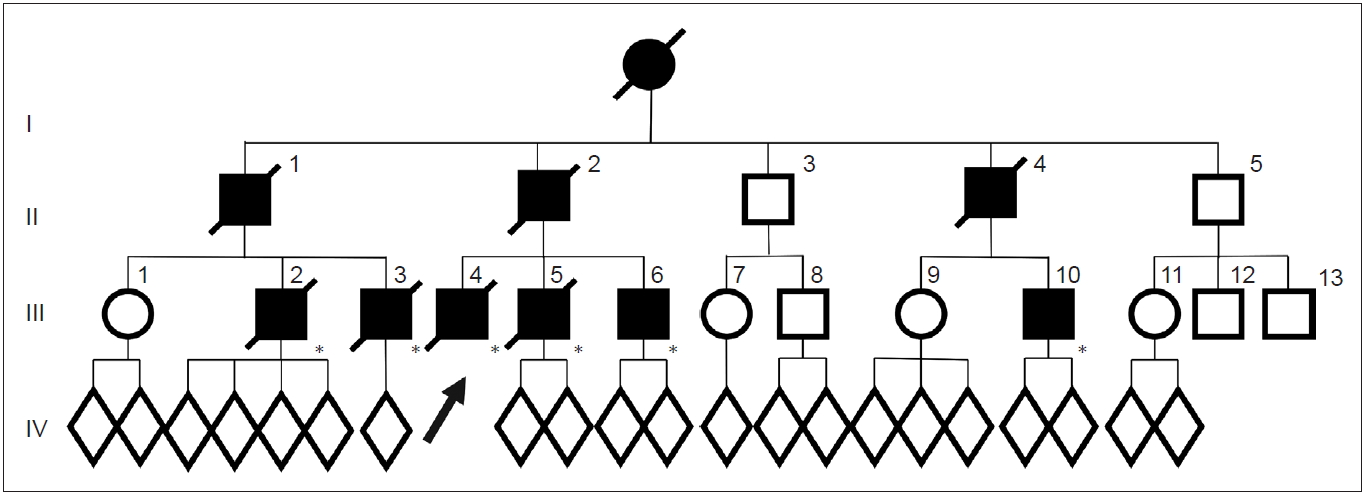

In the FUK-1 family (Figure 1), 10 affected members (9 men) or suspected cases were confirmed for three generations [8]. They did not have problems in movement or mental development, and the average age of onset was 48 years (range: 35–61 years), younger than that in sporadic Parkinson’s disease (PD). The mean duration of disease was 5 years (range: 2–10 years), and this rapidly progressive course is similar to the original Perry syndrome. They also had clinical characteristics such as nonmotor symptoms developing around the time of parkinsonism.

Pedigrees of the FUK-1 family with Perry disease. Circles indicate women. Squares indicate men. The diagonal lines indicate deceased individuals. Black symbols indicate affected individuals. An arrow indicates proband. Asterisks indicate genetically confirmed individual with p.G71A in dynactin I gene. FUK-1: first reported the Fukuoka-1.

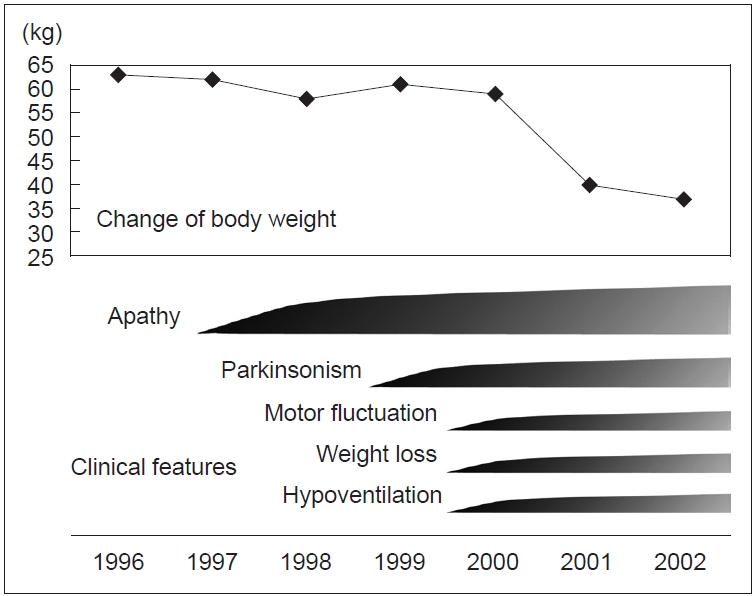

Clinical course of the proband (III-4): At the age of 41 years, his apathy was pointed out by an industrial doctor; at that time, he had difficulty working due to decreased motivation. He visited the Department of Neurology at Fukuoka University Hospital. He did not have complaints but lacked motivation and showed bradykinesia. His facial expressions were poor, and his voice was small with mild rigidity in the neck and extremities. His cognitive function was normal, but he walked forward bending without swinging his arms. He showed postural tremor, and his tendon reflex was active in all extremities without the Babinski sign. He did not show postural instability, dysesthesia, or ataxia. Treatment with levodopa was initiated, and bradykinesia improved. However, unexpectedly, he lost body weight, 10 kg in 2 months, and 15 kg in a year. At the age of 44 years, his bradykinesia deteriorated, and postural instability developed; therefore, he needed partial assistance in daily life temporally. Anxiety and shortness of breath at night developed. He was reevaluated at our hospital, and rigidity, akinesia, and postural instability were remarkable, and the wearing-off phenomenon with dyskinesia was observed. A plain chest X ray, chest CT, and a pulmonary function test were normal. On polysomnography (PSG), central hypoventilation was observed (apnea index, 6.96; mildly abnormal). An arterial blood gas test on room air showed an increased level of PCO2 (47 mm Hg; normal range, 35–45) with normal PO2 (85.2 mm Hg; normal range, 90–105). After he was transferred to another hospital, he was found in a coma in the morning because of CO2 narcosis due to respiratory failure, and he needed mechanical ventilation support. At the age of 46 years, his condition deteriorated due to pneumonia and he died of sepsis.

The proband’s cousin (III-3) manifested neuropsychiatric symptoms such as anxiety at the age of 38 years and was diagnosed with parkinsonism. Levodopa was effective for a while. However, a year later, the wearing-off phenomenon and peak dose dyskinesia developed. At the age of 41 years, hypercapnia developed; at the age of 42 years, he lost 15 kg in body weight in a year. He had repeated episodes of hypercapnia; therefore, he needed tracheotomy and mechanical ventilation. Pneumonia recurred, and he died at the age of 51 years.

The proband’s father (II-2) manifested depression at the age of 43 years. Anti-depressants were administered, but he attempted suicide twice. At the age of 44 years, bradykinesia developed and gradually progressed. At the age of 47 years, akinesia, bradykinesia, resting tremor, and rigidity were observed, and he was diagnosed with PD; levodopa was initiated. At the age of 48 years, he was admitted to the hospital because of respiratory failure, and tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation were necessary. His akinesia worsened, and he became bedridden. Since the onset, he lost 15 kg in body weight. At the age of 49 years, he died of respiratory failure.

The clinical course of this family was similar to that presented in Perry’s original article (Figure 2). Thus, we reported these data to Neurology in 2002 as the first Japanese family with Perry disease [8]. All seven reported families, including this family, presented “classic” Perry syndrome, and later were found to have the DNCT1 gene mutation.

To study the clinicopathology of Perry syndrome and identify the causative gene, we started joint research with the Mayo Clinic in 2001. We succeeded in collecting the data of families with Perry syndrome other than the second Canadian family, which had already been reported at that time. During the research, unreported families with Perry syndrome were newly identified from Hawaii and Japan. Detailed descriptions of the clinical course, brain tissues in autopsy, and DNA samples (74 persons including 17 affected members from 8 families) were collected.

PATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS OF PERRY DISEASE—A NEW TDP-43 PROTEINOPATHY

Pathological reports on Perry disease described neuronal loss in the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus, with rare obvious inclusions and no or few Lewy bodies [1-6]. In previous reports, immunohistochemical staining for α-synuclein had not yet been performed; thus, the pathological study in the FUK-1 family first confirmed the absence of Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra and other sites by α-synuclein antibody immunostaining [8]. Wider et al. [10] also studied the neuropathology of 8 cases of Perry disease and described severe degeneration in the substantia nigra and inclusions with positivity of TDP-43 in residual neurons. The inclusions were observed in the basal ganglia and brain stem, such as the substantia nigra, globus pallidus, neuronal intranuclear inclusions (NII), neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (NCI), dystrophic neurites (DN), and glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCI). The inclusions were positive for ubiquitin but negative for tau and α-synuclein.

TDP-43-positive inclusions were found in ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD-U), frontotemporal dementia-motor neuron disease (FTD-MND), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and they were reported as ubiquitinated NCI, NII, and partial glial inclusions [11,12]. TDP-43 proteinopathy can be classified into six pathological types based on the shape of the inclusions: NCI, NII, DN, axonal spheroid, GCI, and perivascular astrocytic inclusion (PVI) (Figure 3). TDP-43 pathology is mainly associated with ALS, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), and the mixed type of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuron disease (FTLD-MND). Perry disease is characterized by NCI, DN, frequent PVI and spheroids, and its inclusion shape and distribution are different from ALS, FTLD-MND, and hippocampal sclerosis (HpScl). Other than TDP-43 pathology, dynactin p50 inclusions were only observed in Perry disease (Figure 3) but not in ALS, FTLD-MND, or HpScl. Perry syndrome is considered a unique TDP-43 proteinopathy, and inclusions were mainly observed in the substantia nigra, globus pallidus, and brain stem. Only Perry disease has distinct pathological findings of those unique distributions in TDP-43 proteinopathy [13].

Immunohistochemistry for TDP-43 and p50 on tissue from previously reported patients with Perry disease [32]. NCIs in the medullary tegmentum (A), dystrophic neurites in the substantia nigra (B), perivascular astrocytic inclusions in the locus coeruleus (C), spheroids in the substantia nigra (D), oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions in the globus pallidus (E), neuronal intranuclear inclusions in the nucleus basalis of Meynert (F), and p50-positive NCIs in the medullary tegmentum (G). Scale bars = 10 μm (A-G). TDP-43: transactive-response DNA-binding protein of 43 kD, NCI: neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions. Mishima et al. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76:676-682 (41).

TDP-43-positive inclusion is considered specific for FTLD-U, FTD-MND, and ALS. However, TDP-43 inclusions have been found widely in Lewy body disease, Guam Parkinson dementia complex, Alzheimer’s disease, and HpScl [10,14]. Therefore, its specificity is doubtful. Presently, it is considered a common cellular reaction, and its pathological significance is notable. To confirm that TDP-43 is directly involved in the pathogenesis, and the TDP-43 gene (transactive-response DNA binding protein) mutation was shown to cause familial ALS [15]. In Perry disease, FTLD-U, FTD-MND, and ALS, TDP-43-positive inclusions are dominant pathological findings, and they could have a common pathogenesis, different from other diseases, with a combination of α-synuclein- or tau-positive inclusions. Interestingly, the clinical symptoms of Perry disease overlap with sporadic PD despite those facts. Severe neuronal loss in the substantia nigra that is always observed in the pathological findings of Perry disease likely causes clinically progressive parkinsonian syndrome. However, what are pathological backgrounds for other major symptoms, such as apathy, depression, weight loss, and central hypoventilation? We noted the respiratory center in the ventrolateral medulla of the autopsied brain and showed that the density of neurons with positive immunostaining for neurokinin-1 receptors (NK-1R), tyrosine hydroxylase, and tryptophan hydroxylase was significantly decreased [16]. NK-1R-positive neurons in the ventrolateral medulla are considered preBetC neurons, which is important for respiratory rhythm. In animal experiments, the destruction of those neurons leads to impaired respiration, such as irregular respiration and a decreased ventilation response to CO2. Degeneration of preBetC neurons likely causes respiratory symptoms in patients with Perry disease. Additionally, we showed neuronal loss in raphe nuclei (serotonergic neurons), which is another respiratory center. Abnormal serotonergic neurons in the medulla are considered the cause of sudden infant death syndrome. This impaired respiratory center can lead to hypoventilation in Perry disease. Furthermore, a decrease in aminergic neurons in the locus ceruleus and ventral tegmental area was observed that might be associated with depression and apathy. The specific pathological findings that can explain weight loss remain unclear. However, orexin-positive neurons in Meynert’s basal ganglion are decreased in Perry disease, indicating that the dysfunction of the hypothalamus could cause weight loss in Perry disease and might require further detailed neuropathological examination [17].

PERRY DISEASE AND DYNACTIN GENE MUTATION

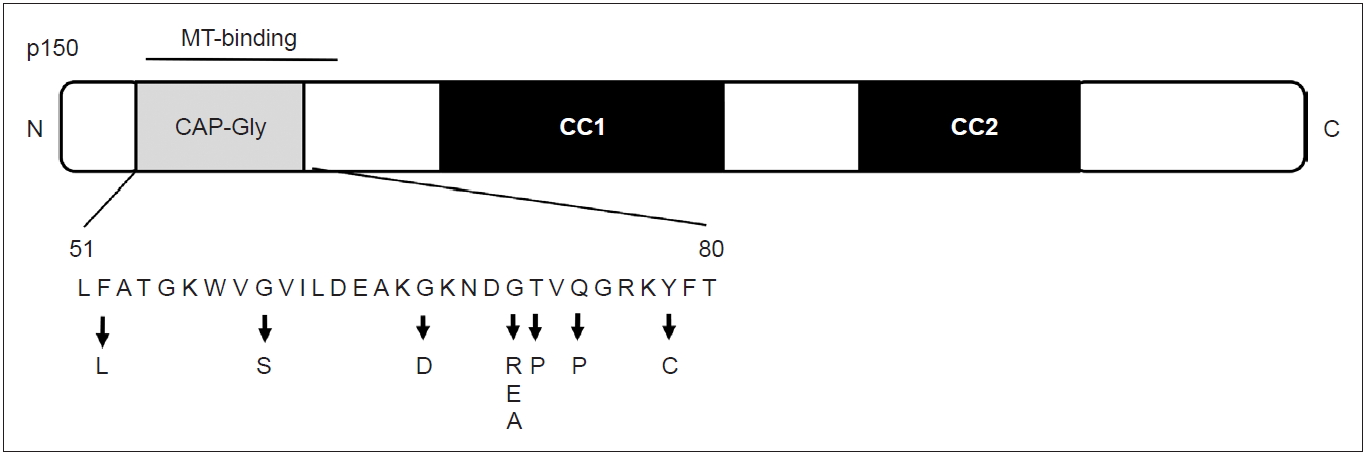

In 2009, we collaborated with the Mayo Clinic and identified the DCTN1 mutation on chromosome 2p in patients with Perry disease [18]. In all 8 families, 5 closely arranged mutations (p.G71A/E/R, p.T72P, p.Q74P) were found in DCTN1 exon 2. Those mutations were not found in the control groups or patients with other familial parkinsonism and were confirmed to be the causative gene.

Before the discovery of the gene mutation in Perry disease, a different point mutation (p.G59S) had been reported in a family with familial spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy [19,20]. Later, other mutations were reported in families with ALS and FTLD, but they have not yet been confirmed to be the causative gene [21,22]. DCTN1 encodes the main subunit p150 glued of the dynactin protein complex [23].

P150 glued exists as a dimer and is a direct connecting site between the dynactin complex and microtubules. Dynactin is associated with cargo transport and retrograde axonal transport among organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Multiple bound complexes, including dynactin, acts with dynein through microtubules and the p150 glued subunit and are involved in various cargo transport through other subunits.

In the N-terminal region of p150 glued, the cytoskeleton-associated protein cytoskeleton-associated protein glycine-rich (CAP-Gly) domain exists [24]. Interestingly, both the five DCTN1 mutations in Perry disease and p.G59S mutation in familial MND exist in the CAP-Gly domain. An experiment showed that, in the MND mutant p.G59S and Perry disease mutant (p.G71R and p.Q74P), the microtubule-binding affinity of p150 glued is decreased [18]. In cells transfected with DCTN1 p.G71R, p.Q74P, and p.G59S, the intracellular distribution of dynactin protein was different from that of the wild type [25]. Thus, the mutant proteins lead to the aggregation of dynactin (toxic gain of function) and loss of function in dynactin/dynein.

CLINICAL DIVERSITY OF PERRY DISEASE

The clinical uniformity of Perry disease has led to the identification of affected families, understanding of its pathogenesis, and the discovery of the causative gene. Since the discovery of the gene, familial parkinsonism has been screened worldwide, and not only “classic” clinical manifestations are considered but also diverse phenotypes in patients with Perry disease. Since the discovery of DCTN1 mutation in 2009, 14 families have been newly reported (Table 1). Eight pathogenic mutations (p.F52L, p.G67D, p.G71A/E/R, p.T72P, p.Q74P, and p.Y78C) have been discovered to date (Figure 4), elucidating the diverse phenotypes of the same gene mutation. In 2010, a family with DCTN1-p. G71R mutation was newly identified. The proband presented disinhibition, axial rigidity, frequent falls, and downward gaze palsy. MRI findings revealed midbrain atrophy similar to the phenotype of progressive nuclear palsy. Levodopa was responsive to parkinsonism initially. Later, he showed central hypoventilation characteristic of Perry disease, but his clinical course has been different from the classic type [26]. Another patient from the UK manifested anxiety and depression; in his mid-forties, he developed hypotension, neck rigidity, apraxia of eyelid opening, and behavioral abnormalities, including disinhibition due to dysfunction of the frontal and temporal lobes and midbrain. Later, he developed weight loss and central hypoventilation and was diagnosed with Perry disease with DCTN1-p.G67D mutation [27]. The age of onset varied widely among affected individuals in the same family from Japan (FUK-4/DCTN1-p.F52L), whose progression was relatively slow and included a member with onset at age 70 years [28]. One of them showed marked atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes and midbrain during long-term hospitalization under mechanical ventilation. From Korea, three families with DCTN1 mutation were reported, and they included patients with oculogyric crisis and supranuclear gaze palsy [29]. Of 21 families diagnosed with familial progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), one family had DCTN1-p.G71E. Two members of this family had PSP-like symptoms, and one had typical Perry disease. In the clinical course, various symptoms developed, such as behavior abnormalities associated with FTLD, apathy, eyelid twitching, grasp reflexion, tongue apraxia, and dystonia. The effect of levodopa was limited, and levodopa-induced dyskinesia and hallucination were manifested [30]. In two Asian patients who had been diagnosed with familial parkinsonism, later clinically diagnosed with PSP, DNA screening identified DCTN1-p.K56R in the patients. However, we did not include this report in our Table 1 because it did not describe the details of their clinical course including the characteristic symptoms of Perry disease [31].

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA OF PERRY DISEASE

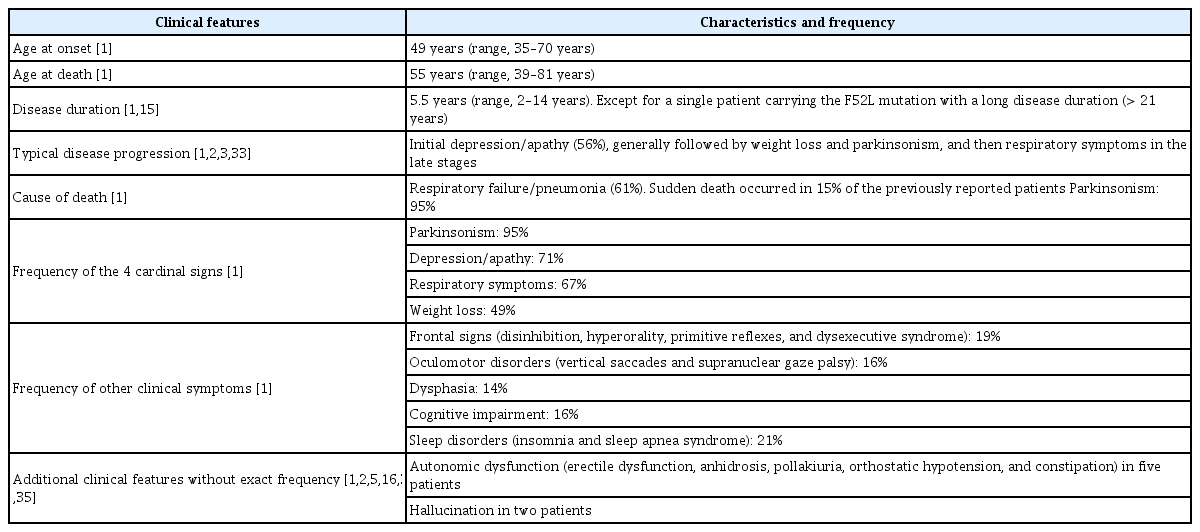

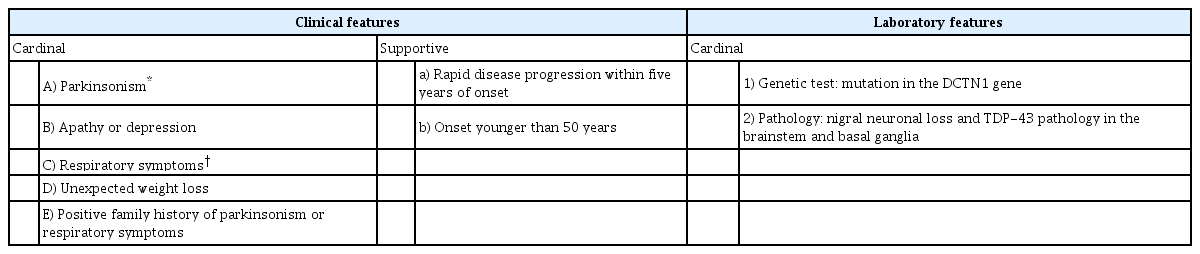

Since the discovery of the dynactin gene abnormality in 2009, more than 20 families have been reported during these 10 years. Early detection of Perry disease is still difficult; in most cases, the patients are diagnosed with PD or progressive supranuclear palsy until marked weight loss or central hypoventilation develops. In some cases, the patients die of respiratory failure abruptly, making the diagnosis more difficult before death. Some patients with Perry disease diagnosed by gene mutation manifested differently from classic Perry syndrome, and it was necessary to establish the unified international diagnostic criteria before death. The research, which promoted an international joint research, analyzed 87 previously reported cases and the results are shown in Table 2 [32]. The clinical diagnostic criteria for patients with confirmed DCTN1 mutation are shown in Table 3. Four major signs are parkinsonism, apathy or depression, central hypoventilation, and unexpected weight loss, which were also described in the original article by Perry. Approximately 35% of patients had all four major signs at diagnosis; however, the four signs generally developed gradually in the clinical course [32].

Parkinsonism includes rigidity (60%), tremor (52%), bradykinesia (38%), and postural instability (23%), which are usually more symmetrical than sporadic Parkinson disease. Although there are various descriptions regarding levodopa responsiveness in the previous reports, for most of the cases, including ours, levodopa was effective when used in the early stage, but motor complications appeared early and the effect was eventually diminished [1,2,8]. In some cases, such as sporadic PD, motor complications associated with levodopa were observed [8,26,28-30,33]. We reported a case with impulse control disorder and punding seen in the clinical course [33].

More than 70% of patients show depression or apathy, which is characteristic of this disease. Central hypoventilation is life-threating feature in cases with Perry disease and is observed in approximately 70% of patients; attention must be given to this manifestation. Respiratory failure is sometimes unpredictable; however, some patients show tachypnea or dyspnea before respiratory failure. PSG performed in some patients showed irregular respiration and apnea during sleep. Apnea in PSG revealed central-type hypoventilation because no contradictory movement of the chest and abdominal wall was detected. When apnea is prolonged, it can lead to sudden death [34]. Unexpected weight loss usually presents after parkinsonism manifests, and it decreases rapidly, mostly 10–15 kg of loss in a year; the weight loss then stops at a low weight level.

In the diagnostic criteria, imaging findings are described as supporting features. MRI reveals normal findings or atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes or midbrain [26,28-30]. On single-photon emission CT (SPECT) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET), decreased blood flow and decreased metabolism are observed in the frontal and temporal lobes [29,30,33].

On a dopamine transporter image using SPECT or PET, uptake in the striatum was consistently decreased. This manifestation was also shown in a gene mutation carrier (T72P) who had not yet developed symptoms; therefore, degeneration of striatonigral neurons occurs before a carrier manifests symptoms [28,29,35]. On metaiodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy, which evaluates cardiac sympathetic nerve terminal, a decrease was shown in two patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Perry disease was identified only by symptomatology until 2009; however, presently, it should be regarded as a single clinical, pathological, and genetic entity. Thus, we proposed to change the name from syndrome to disease in 2018 [32]. Perry disease is characterized clinically mainly by parkinsonism, apathy-depression, unexpected weight loss and central hypoventilation, and pathologically by TDP-43 proteinopathy. Its symptoms are similar to sporadic PD in the early stage of disease because of the symptoms, treatment effect with levodopa, and presence of motor complications. Nonmotor symptoms of Perry disease, such as weight loss, depression, apathy, sleep disturbance, and respiratory dysfunction, are also seen in sporadic PD to some extent. Thus, some features of Perry disease clinically and pathologically overlap with other sporadic neurodegenerative diseases and are genetically shared with other MNDs. In the future, research to elucidate the pathogenesis of Perry disease should also be associated with other sporadic or familial neurodegenerative diseases (PD, multiple system atrophy, FTLD-U, or ALS).

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Yoshio Tsuboi. Data curation: all authors. Formal analysis: Yoshio Tsuboi, Takayasu Mishima. Funding acquisition: Yoshio Tsuboi, Takayasu Mishima. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: Yoshio Tsuboi. Project administration: Yoshio Tsuboi. Resources: all authors. Software: Yoshio Tsuboi. Supervision: Yoshio Tsuboi. Validation: Takayasu Mishima, Shinsuke Fujioka. Visualization: Yoshio Tsuboi, Takayasu Mishima. Writing—original draft: Yoshio Tsuboi. Writing—review & editing: Takayasu Mishima. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients with Perry disease and their families who cooperated with this study.

This paper was supported by JSPS KAKENHI and Research on Rare and Intractable Diseases, Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants.