Generalized Chorea Due to Secondary Polycythemia Responding to Phlebotomy

Article information

Dear Editor,

Chorea can be seen in association with polycythemia rubra vera (PV) or primary polycythemia, especially in elderly women. However, chorea due to secondary polycythemia is rare, and we report a case in an adolescent boy due to congenital cyanotic heart disease and its rewarding response to phlebotomy.

A 15-year-old boy, born of non-consanguineous parentage, with cyanotic spells since 6 months of age, was found to have ventricular septal defect and pulmonary atresia for which he underwent placement of a bidirectional Glenn shunt and left pulmonary artery plasty at 12 years of age. He presented to us with a 2-month history of abnormal fidgety movements and difficulties with feeding and holding objects. There was no previous history of rheumatic fever nor were there any recent infections or drug exposure. Family history was negative for chorea. Physical examination showed facial dysmorphism in the form of hypertelorism, a low hair line, low-set ears and webbed neck. He had central cyanosis and pandigital clubbing, with a resting oxygen saturation of 75%. He was noted to have generalized chorea of all four limbs (right > left), facial chorea, variable tone in upper and lower limbs (segment 1, Supplementary Video 1 in the online-only Data Supplement) and a choreic gait. Muscle power and reflexes were normal, and there were no cerebellar signs. Routine blood evaluation showed a hemoglobin level of 22 g/dL with a hematocrit of 70%. Serum calcium, phosphorus and intact parathyroid hormone levels were within normal limits. Results of serum antistreptolysin O titer, vasculitis workup and autoimmune encephalitis panel were negative. Non-contrast CT of the brain revealed no structural pathology to account for his symptoms, except for dense blood vessels secondary to increased hematocrit (Supplementary Figure 1A and B in the online-only Data Supplement). MRI of the brain (axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) (Supplementary Figure 1C in the online-only Data Supplement) was normal and susceptibility weighted imaging sequences (Supplementary Figure 1D in the online-only Data Supplement) showed susceptibility artifacts involving cerebral venous structures consistent with polycythemia.

He was initially given a trial of tetrabenazine that failed and 6 weeks later a trial of intravenous methylprednisolone was empirically given for 3 days, for possible autoimmune etiologies of chorea, without any relief. Two months later, he underwent three sessions of phlebotomy on alternate days (10 mL/kg/session) to reduce the hematocrit to 57%, upon which he had a remarkable reduction in choreiform movements over the ensuing fortnight (segment 2, Supplementary Video 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). At one-year follow-up, he continued to be asymptomatic.

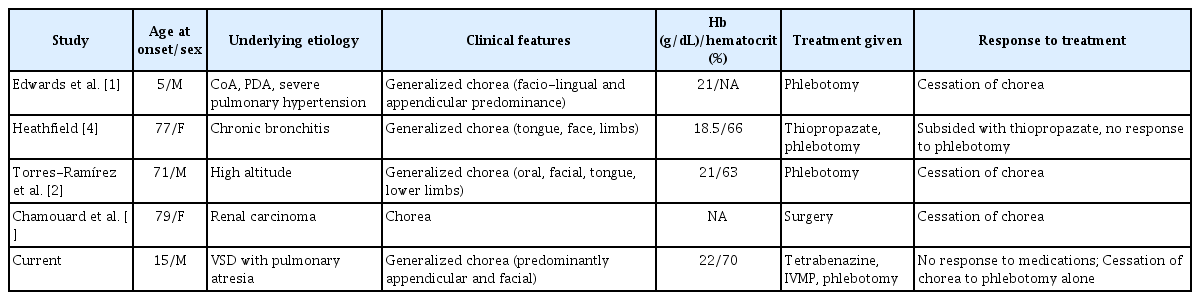

Chorea due to secondary polycythemia is a rare manifestation, and only 4 cases have been reported in the literature to date, 3 of which were in very elderly patients (Table 1). In two of these cases, patients improved with phlebotomy [1,2], and the third improved after surgical removal of the tumor [3]. However, Heathfield’s patient with chronic bronchitis failed to respond to venesection, and control was achieved with thiopropazate [4]. Our study is the second reported [1] case due to cyanotic heart disease-induced polycythemia, with a similar rewarding response to phlebotomy. A lag in therapeutic response by as much as a fortnight may be seen.

The incidence of chorea is approximately 1–2.5% among those with PV. A review of 24 case reports of PV since 1960 showed that structural imaging studies in patients with polycythemic chorea were often non-contributory, as in our case [5]. Elevated hematocrit levels cause hyperviscosity, which in turn leads to sluggish blood flow and reduced oxygen delivery to the basal ganglia, especially the nigro-striatal, pallido-thalamic and pallidoluysian circuits. However functional imaging, with single photon emission computed tomography in choreic and non-choreic states, does not reveal any perfusion defects suggesting that reduced cerebral blood flow may not be the mechanism [6]. Chorea is a known adverse effect of oral contraceptive pills, and estrogen is known to affect dopamine receptor sensitivity in the striatum. Increased dopamine release by platelet congestion in cerebral vessels in the striatum, which exhibits altered dopaminergic sensitivity due to estrogen deficits, in postmenopausal women is another hypothesis [1]. This may explain the increased incidence of chorea in elderly females, although PV itself is more common in males. PV, a myeloproliferative disorder due to the clonal expansion of red blood cells, is associated with gain-of-function JAK2 V617F gene mutation. JAK2 inhibition is neuroprotective. The presence of chorea in PV is considered to be due to the expression of JAK2 in the striatum, with activation leading to astrogliosis and inflammation, suggesting the possibility of a direct mechanism for chorea, without the presence of polycythemia [7].

Various hypotheses have been postulated for the mechanism of chorea in secondary polycythemia, which is characterized by elevated hemoglobin and hematocrit levels without a JAK2 mutation. The response to phlebotomy, in the majority cases of secondary polycythemia, suggests the role of increased hematocrit. In secondary polycythemia, a critical threshold may be present for hematocrit levels in susceptible individuals beyond which the movement disorder manifests. Our patient showed high hemoglobin levels even before his presentation with chorea, although the values hovered at approximately 18 g/dL. However, when he presented with a movement disorder, his hemoglobin value was 22 g/dL, suggesting that a critical threshold may be present in susceptible individuals before the onset of chorea. In the documented cases (Table 1) of secondary polycythemia with chorea, all subjects who had responded to phlebotomy were associated with very high hemoglobin levels (> 20 g/dL) at the time of chorea. The response to phlebotomy was rapid and was usually seen within a few days of the procedure, suggesting that it is commensurate with a reduction in hemoglobin and is often sustained once hematocrit is maintained below this critical level. It is still unknown why very few patients with polycythemia develop chorea. Treatment of polycythemia with phlebotomy not only ameliorates chorea but also averts other major neurological complications, such as cerebral venous thrombosis or stroke. Long-term follow-up of individuals is suggested to assess the recurrence of chorea. If future relapses are also associated with similar increase in hemoglobin, and favorable responses to phlebotomy, it will empower current hypothesis. This approach would help confirm this purported critical threshold theory and support the existing data.

Our case highlights that chorea can occur in adolescents due to secondary polycythemia, and recognition of this rare entity is essential to avoid treatment delay, as this condition responds dramatically to phlebotomy.

Notes

Ethical Compliance Statement

Written informed consent was obtained per the institute guidelines for videotaping the subject and publishing his video and history.

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ajith Cherian, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu. Data curation: Ajith Cherian, Naveen Kumar Paramasivan, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu. Formal analysis: all authors. Investigation: Ajith Cherian, Naveen Kumar Paramasivan, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu. Methodology: Ajith Cherian, Naveen Kumar Paramasivan, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu. Resources: all authors. Supervision: Ajith Cherian, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu, Syam Krishnan, Amitha Radhakrishnan Nair. Validation: Ajith Cherian, Naveen Kumar Paramasivan, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu. Visualization: Ajith Cherian, Naveen Kumar Paramasivan, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu. Writing—original draft: Ajith Cherian, Naveen Kumar Paramasivan, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu. Writing—review & editing: Ajith Cherian, Divya Kalikavil Puthanveedu.

Acknowledgements

None.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.20081.

Segment 1 (before phlebotomy): Note the generalized chorea (asymmetric right >left) with facial choreiform movements “huffing puffing” and frontalis overactivity. Pandigital clubbing is seen in both upper and lower limbs. Segment 2 (post phlebotomy): There is significant reduction in chorea with a remarkable improvement in disability

Non-contrast CT of the brain (A and B) was normal except for hyperdense intracranial arteries and dural venous sinuses secondary to increased hematocrit. MRI of the brain (axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) (C) showed no structural pathology, and susceptibility weighted imaging sequences (D) showed susceptibility artifacts involving the cerebral venous structures consistent with polycythemia.